Our journey into creating TerraForge began with extensive research, involving more than 40 tabs open for weeks, as we delved into the best methods for generating voxels. Despite the overwhelming variety of techniques and approaches, I opted to start simple. Over the past few months, I’ve immersed myself in C++ within Unreal Engine, where every line of code has been a new learning experience. The countless hours spent combing through Unreal’s documentation have proven invaluable. Tackling procedural voxel generation has been both challenging and exhilarating. Some might argue that this project is too complex for a first complete endeavor, but I thrive on such challenges. Here’s a rundown of the progress made so far and a glimpse into what the future holds.

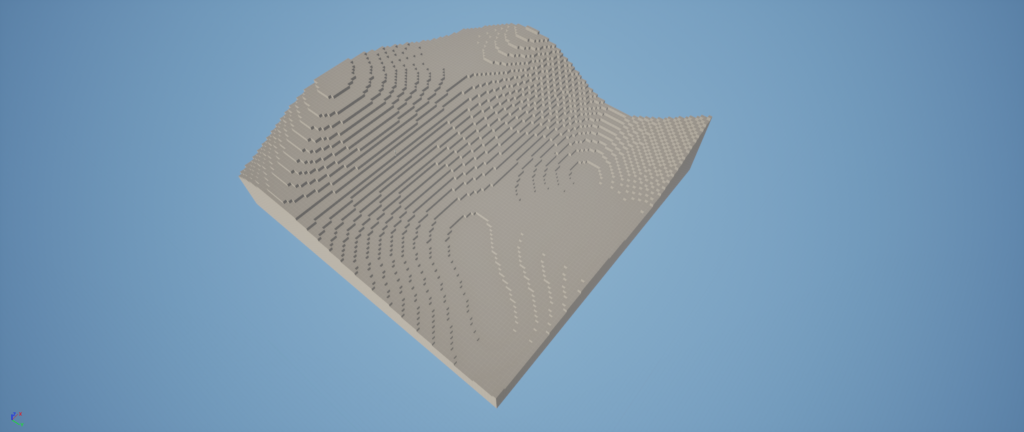

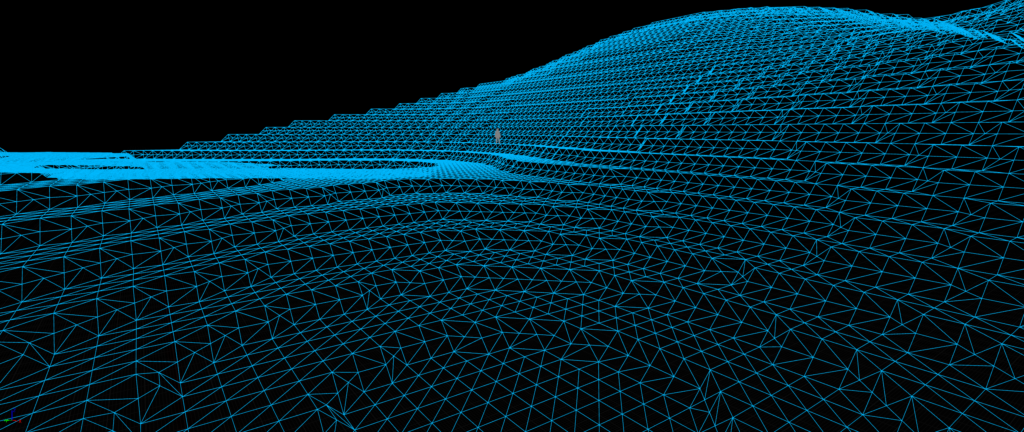

Simple Voxel Generation in Chunks

This unfamiliar territory wouldn’t have been navigable without the guidance of experienced natives. I owe much of my foundational understanding to CodeBlaze, whose series of tutorials on voxel terrain generation have been instrumental. His solutions, though simple, lay the groundwork for any voxel system, and his clear explanations have been crucial. I watched his videos repeatedly and meticulously followed every recommendation he provided.

Generating and storing each voxel individually has resulted in excessive memory consumption. The initial implementation led to several crashes in Unreal Engine, especially when trying to load numerous chunks simultaneously. This issue has highlighted the need for a more memory-efficient approach to voxel generation and storage.

To tackle this problem, I revisited the wealth of resources and community advice available. CodeBlaze’s tutorials provided a strong foundation, but the scale of this project requires more advanced techniques. Exploring various methods and best practices for memory-efficient voxel management has been crucial.

One potential solution involves optimizing the way voxels are stored and managed. Instead of storing each voxel individually, we can use data structures that aggregate voxel data and only store necessary information. Sparse voxel octrees (SVOs) and voxel data compression techniques are promising avenues to explore. These methods allow for efficient representation of large voxel spaces by only storing non-empty regions or aggregating similar voxels.

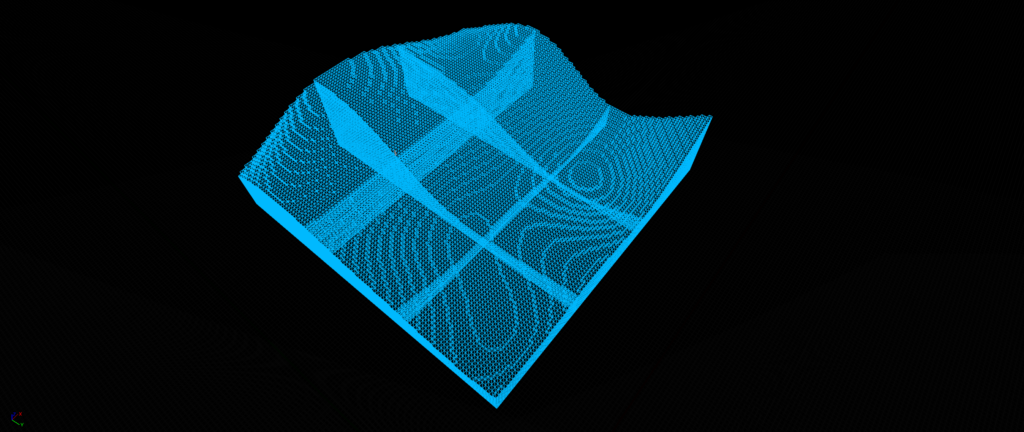

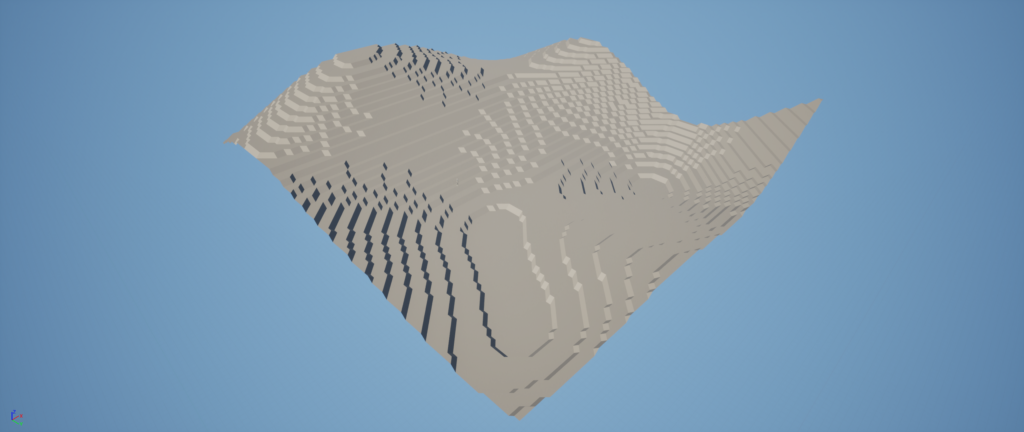

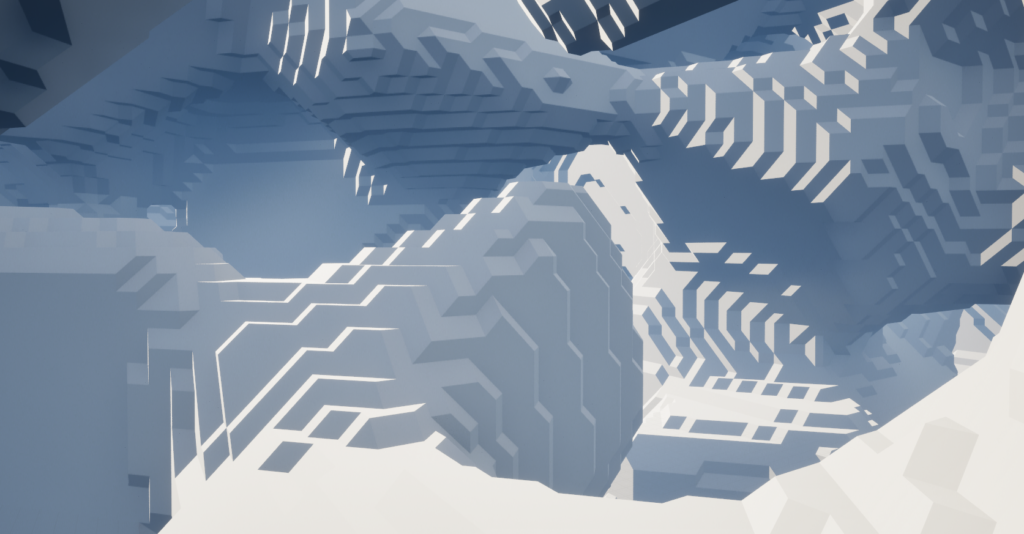

Greedy Chunks

Another great solution is using greedy meshing. We basically check the faces of the chunks and try to merge them, reducing memory usage. Here is a great video explaining it in more detail, and here is a comprehensive article on the topic.

As you can see, we have much larger and therefore fewer voxels than before. It’s a very effective approach, allowing me to create many chunks without much memory issues. However, for our project, our goal is to create planets, using chunks as they are traditionally implemented in flat-surface voxel games may not be the best solution for separating voxels into groups on a spherical surface. This will also be discussed again later in this post discuss this more later.

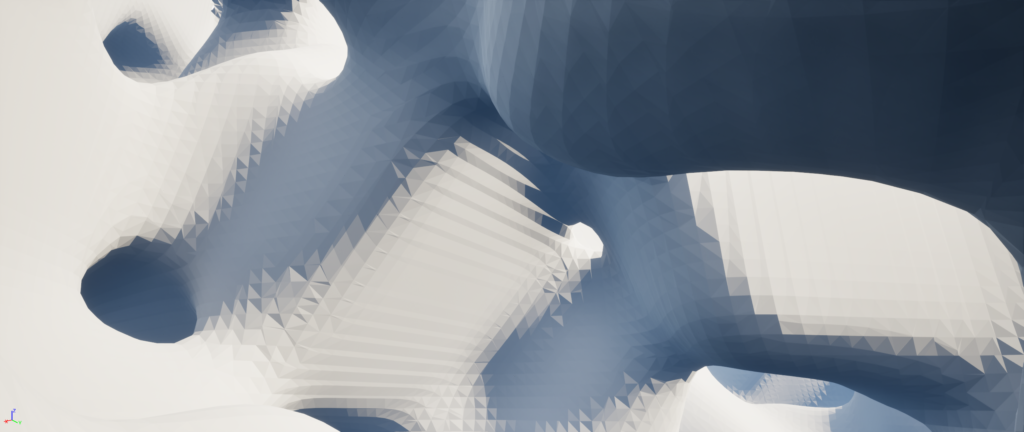

Marching Cubes

Marching Cubes is a very popular method used by some big games. Using the initial method I mentioned, we apply interpolation between the voxels to create smooth terrain. Here are some references:

- Coding Adventure: Marching Cubes

- Polygonising a Scalar Field

- NVIDIA Procedural Terrains

- Marching Cubes: A High-Resolution 3D Surface Construction Algorithm

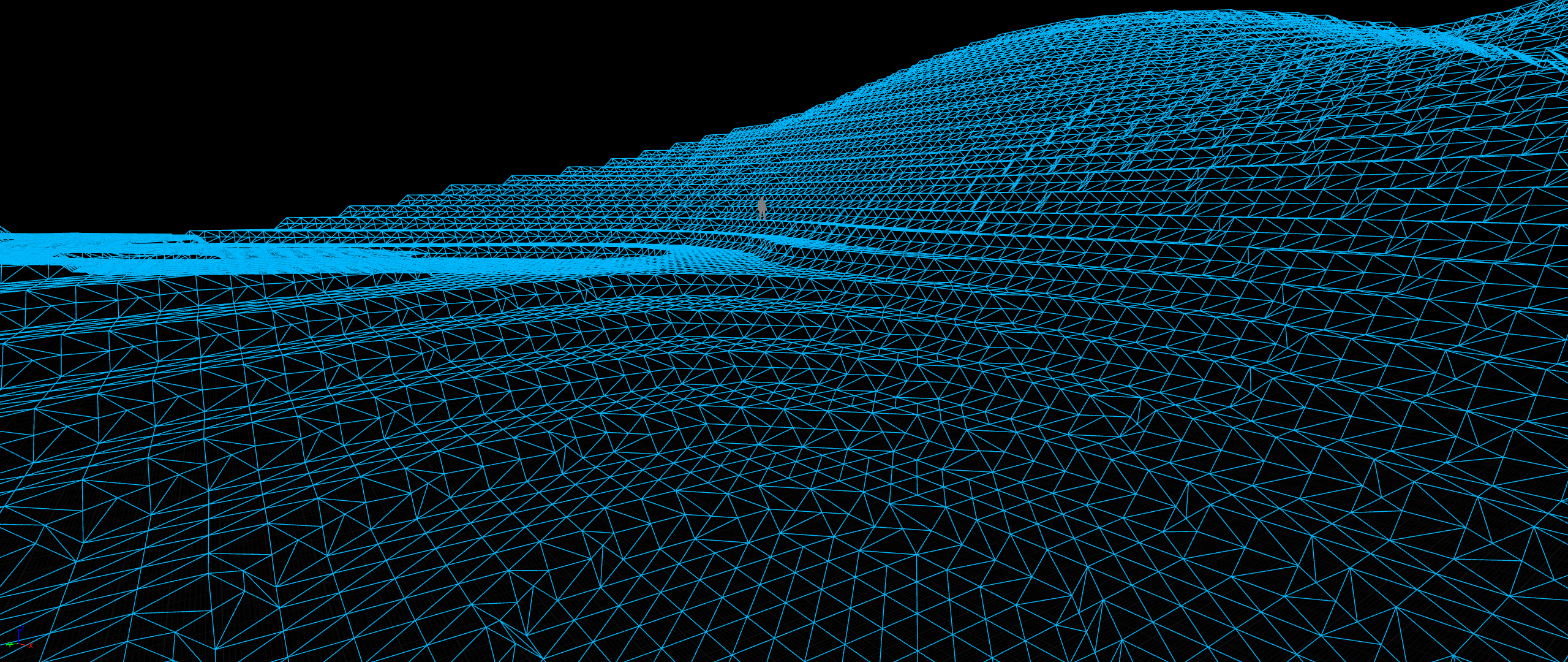

As you can see, there are many vertices. Marching Cubes can be computationally expensive, though there are ways to optimize it. However, the question remains: how do we create a sphere efficiently with this method? There are solutions, but I’m unsure how efficient they would be on a large scale. This leads to the next thought.

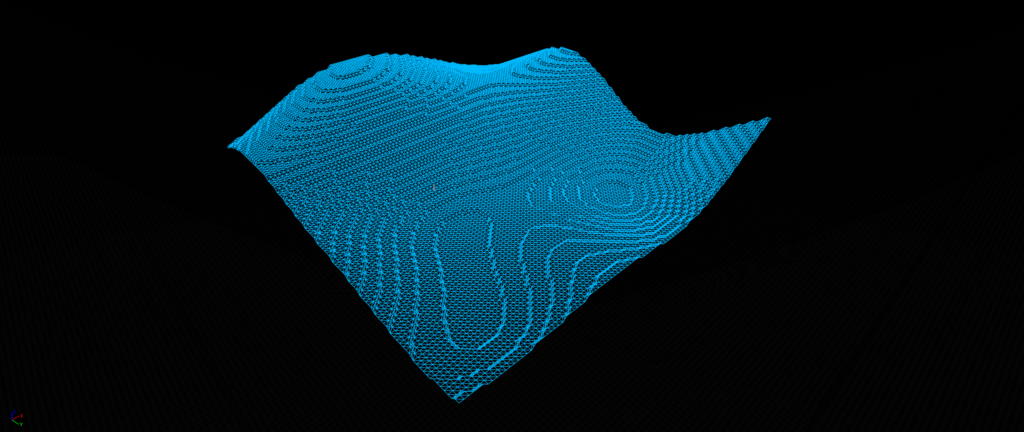

Fibonacci Delaunay Voronoi Sphere

Of all the solutions we have discussed thus far this solution seems quite effective at solving most of the major issues we’ve discussed. The Fibonacci sequence is undeniably beautiful. This paper explains in detail how it works. We create a sphere using the Fibonacci sequence, and with these points, we can generate terrain and then “Wrap” terrain over it. Although this is still an early idea, we are exploring how to apply it effectively. In the end, it won’t be a voxel terrain anymore—that’s the beauty of it. After extensive research, this seems to be quite a promising possibility. Once we implement this solution, we’ll revisit this topic and share our findings and some benchmark scores as we progress through out implementation.